Introduction

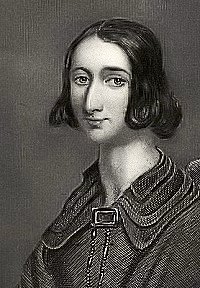

Born: June 2, 1816, Hackney, England.

Died: September 16, 1847, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Buried: Alter Jüdischer Friedhof, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Born: June 2, 1816, Hackney, England.

Died: September 16, 1847, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Buried: Alter Jüdischer Friedhof, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Aguilar was the oldest child of parents descended from Portuguese Marranos who sought asylum in England in the 18th Century. To strengthen her constitution, which from infancy had been feeble, she was taken to the seashore and to various rural locations in England.

Her love of nature was cultivated by these experiences; and at the age of 12 she devoted herself of her own accord to the study of natural science, augmenting a collection of shells she began at Hastings, when only four years old, and supplementing it by mineralogical and botanical collections.

Grace was educated mainly by her parents. Her mother, a cultivated woman of strong religious feeling, trained her to read the Scriptures systematically; and when she was 14, her father read aloud to her regularly, chiefly history, while she was occupied with drawing and needlework.

She was an assiduous musician till her health became impaired. Her reading, especially in history, was extensive; her knowledge of foreign literature was wide.

She evinced a literary tendency at the age of seven, when she began a diary, which she continued almost uninterrupted until her death. Before she was 12, she had written a drama, Gustavus Vasa. Her first verses were evoked two years later by the scenery about Tavistock in Devon. The first products of her pen to be published (anonymously in 1835) were her collected poems, which she issued under the title The Magic Wreath.

Her productions are chiefly stories and religious works dealing with Jewish subjects. The former embrace domestic tales, stories based on Marrano history, and a romance of Scottish history, The Days of Bruce (1852).

The most popular of the Jewish tales is The Vale of Cedars, or the Martyr: A Story of Spain in the 15th Century, written before 1835, published in 1850, and twice translated into German and twice into Hebrew.

Her other stories founded on Jewish episodes are included in a collection of nineteen tales, Home Scenes and Heart Studies (published posthumously in 1852); The Perez Family (1843) and The Edict, together with The Escape, had appeared as two separate volumes; the others were reprinted from magazines.

Her domestic tales are Home Influence (1847) and its sequel, The Mother’s Recompense (1850), both of them written early in 1836, Woman’s Friendship (1851), and Helon: A Fragment from Jewish History (1852).

The first of Aguilar’s religious works was a translation of the French version of Israel Defended, by the Marrano Orobio de Castro, printed for private circulation.

It was closely followed by The Spirit of Judaism, the publication of which was for a time prevented by the loss of the original manuscript. Sermons by Rabbi Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia, had fallen into her hands and, like all other accessible Jewish works, had been eagerly read. She requested him to revise the manuscript of the Spirit of Judaism, which was forwarded to him, but was lost. Grace rewrote it; and in 1842 it was published in Philadelphia, with notes by Leeser.

A second edition was issued in 1849 by the first American Jewish Publication Society; and a third (Cincinnati, 1864) has an appendix containing 32 poems (bearing dates 1838–47), all but two reprinted from The Occident. The editor’s notes serve mainly to mark dissent from Aguilar’s depreciation of Jewish tradition—due probably to her Marrano ancestry and to her country life, cut off from association with Jews.

In 1845 The Women of Israel appeared—a series of portraits delineated according to the Scriptures and Josephus.

This was soon followed by The Jewish Faith: Its Spiritual Consolation, Moral Guidance, and Immortal Hope, in 31 letters, the last dated September 1846. Of this work—addressed to a Jewess influenced by Christianity, to demonstrate to her the spirituality of Judaism—the larger part is devoted to immortality in the Old Testament.

Aguilar’s other religious writings—some of them written as early as 1836—were collected in a volume of Essays and Miscellanies (1851–52). The first part consists of Sabbath Thoughts on Scriptural passages and prophecies; the second, of Communings for the family circle.

In her religious writings, Aguilar’s attitude was defensive. Despite her almost exclusive intercourse with Christians and her lack of prejudice, her purpose, apparently, was to equip English Jewesses with arguments against conversion.

She inveighed against formalism, and stressed knowledge of Jewish history and the Hebrew language. In view of the neglect of the latter by women (to whom she confined her expostulations), she constantly pleaded for the reading of the Scriptures in the English version.

Her interest in the reform movement was deep; yet, despite her attitude toward tradition, she observed ritual ordinances punctiliously. Her last work was a sketch of the History of the Jews in England, written for Chambers’ Miscellany.

In style, it is the most finished of her productions, free from the exuberances and redundancies that mark the tales—published, for the most part, posthumously by her mother. With her extraordinary industry—she rose early and used her day systematically—and her growing ability of concentration, she gave promise of noteworthy work.

Aguilar’s later years were full of family trials. In 1835 she had an illness, from whose effects she never recovered. Finally, her increasing weakness and suffering necessitated a change of air, and in 1847 a Continental trip was arranged.

Before her departure, some Jewish ladies of London presented her with a gift and a touching address recounting her achievements in behalf of Judaism and Jewish women.

She visited her elder brother in Frankfurt, and at first seemed to benefit from the change; but after a few weeks she had to resort to the baths of Schwalbach.

Alarming symptoms forced her return to Frankfurt, where she died. Her last words, spelled on her fingers, were, Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him.